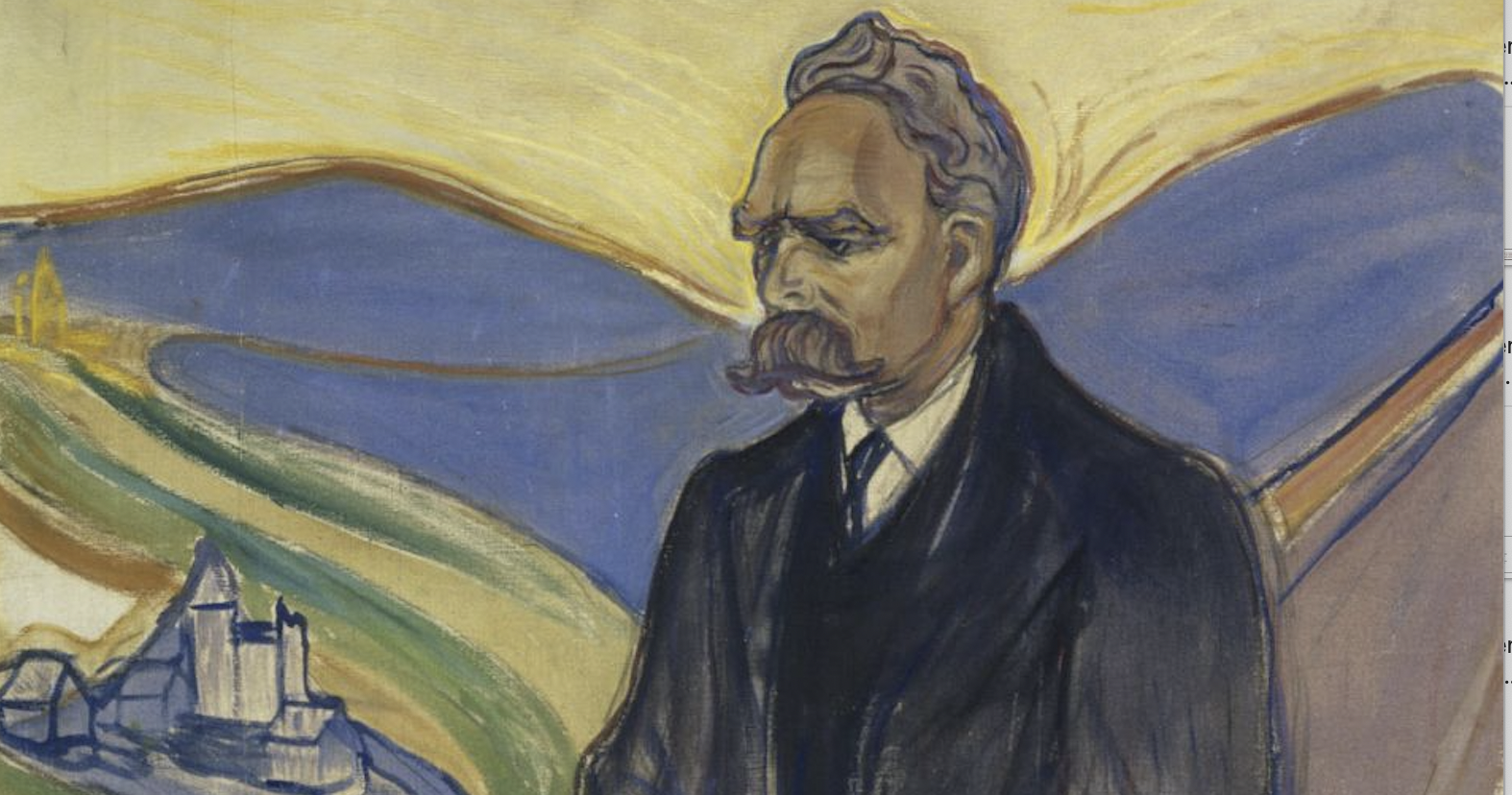

Walking With Nietzsche- Published in IM-1776, October 2022

A Tour Through Friedrich Nietzsche's Favorite Cities and Walks

“Friedrich Nietzsche knew the fullness of spirit that tempts the unknown;

the Will to Power that drives the hero.”

— Plaque at Piazza Carlo Alberto, Turin

“All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

Like Thoreau, Beethoven, and Darwin before him, Friedrich Nietzsche was known to take walks alone, sometimes up to eight hours a day. The German philosopher would carry a notepad with him and pen down thoughts as he walked. The walks, meant to help clear his complex, genius mind, clearly stimulated him. Entire sections of his great Thus Spoke Zarathustra were written on foot.

For Henry Thoreau, walking was a creative, mental and spiritual practice. He emphasized the importance of walking without a defined goal, an attempt to free the mind from restrictions. The relinquishing of the physical map allows your brain to build new mental models. The sense of adventure and the risk associated with not knowing where you are going contrasts with a newfound trust that can be located in the body. There is a wild and intelligent animal inside each of us, of which Nietzsche would indeed have agreed.

As a lifelong runner, running became far less appealing to me after spending more time in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, two climates that over-heated my English nature. I started walking around four miles most mornings, then six, and eventually up to eight. Some of my most joyous moments and significant change in my well-being came thanks to no doctor, medication, or coach, but from walking, especially while getting lost on a daily stroll.

In the hope of channeling a little more of Nietzsche’s will, last summer, two friends and I decided to follow in his footsteps…

Sorrento

“When for the first time I saw the evening rise with its red and gray softened in the Naples sky, it was like a shiver, as though pitying myself for starting my life by being old, and the tears came to me and the feeling of having been saved at the very last second.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, on Sorrento

An Italian coastal town 30 miles south of Naples, in Sorrento Nietzsche found the inspiration that eventually made him give up his teaching position to focus solely on philosophy. This is where, amidst long walks down the Italian coastline, he began penning his first great philosophical treatise, Human, All Too Human.

Nietzsche was in Italy with his philosopher friend Paul Rée on the invitation of German writer Malwida von Meysenburg. Malwida’s name is no longer well-known, but in 19th Century literary circles, she was a recognized political commentator and an early feminist. (An English translation of her vivacious autobiography, Memoirs of an Idealist, can be found here.)

Nietzsche made the most of his six months in Sorrento. Despite never being a man of good health, he would take long walks in the morning, often before the sun had risen and for several hours. After joining Rée and Malwida for lunch, they would walk again as a group or visit historical attractions before returning to read and talk.

The nearby Hotel Vittoria, where my friends and I stayed, is known as one of Nietzsche’s favorites. Their friends, the composer Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima, were also known to stay there. Nietzsche, Malwida, and Rée all highlighted in their personal reflections that these days were some of the happiest of their lives. If you haven’t visited Sorrento or spent days walking the Italian coastline, I advise you to try it.

The Hotel Vittoria still stands as exquisitely as it once did for the Wagners. The three of us sat on the terrace just as they once did, plotting our adventurous walks. On one memorable occasion, we drove towards Naples to Lake Averna, where Ovid laid Sybil’s Grotto and the entrance to the River Styx. After walking for miles amongst Roman ruins, we found ourselves at the entrance of Sybil’s ominous cave, just as described in Book Six of The Aeneid. Not having found the courage to descend to the bottom, we wondered if Nietzsche and his friends ever could.

France

“I can picture myself a couple of philosophic flaneurs with serious eyes and smiling lips, strolling through the boulevards and becoming well-known figures in the museums and libraries, in the Closerie des Lilas and in the cool recesses of Notre Dame.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, letter to his sister Elizabeth

As a young man, Nietzsche, an ardent admirer of French literature, fantasized about long, leisurely walks in Paris. Although he never made it to the French capital (later concerned by his sensitivity to “environmental electricity,” which he believed to be detrimental to his health), Nietzsche spent five winters in Nice, Southern France, between 1883 and 1887.

Parisans may have been too energetically irritating for Nietzsche. But the Niçois region didn’t feel entirely French; it had only been purchased and integrated into France two decades earlier. Nice also had a good reputation among physicians for its air quality and mild temperatures, which suited Nietzsche, who broadly traveled in search of optimizing his health.

Nietzsche’s favorite long walks across the French Riviera included Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat and the medieval town of Èze. This is where he conceived major parts of Zarathustra, writing of it as being “conceived during an ascent of the most painful from the station to the magnificent Moorish village Eze, built in the middle of cliffs.”

The path that Nietzsche took is documented, so I followed him in his walking again (this time solo), starting with the Le Chemin de Nietzsche from the Hotel Cap Estel, the exact hiking trail Nietzsche took almost daily, now dedicated to him. The 2.5-mile arduous ascent with coastal views of the Mediterranean, which goes from the village of Èze bord-de-Mer to the main town of Èze, is perhaps the most beautiful hike I had ever summited, crowned by Èze’s Église Notre-Dame-de-l’Assomption, perhaps also the most sublime church I had ever seen. I imagined Nietzsche after a long ascent taking a rest in the same church pews, questioning if the beauty of such a place ever made him doubt his comment about Christianity being “life-denying.”

On Le Chemin de Nietzsche, one can see how such a dramatic landscape, ragged cliffs contrasted with an endless smooth sea, could become part of the background setting of Nietzsche’s texts. Zarathustra’s Chapter XLV, The Wanderer, is recognizably set amongst this specific trail and the route is now marked by signposts with extracts of his text:

“And when he had reached the top of the mountain ridge, behold, there lay the other sea spread out before him: and he stood still and was long silent.”

The Final Walk

“Autumn here was a permanent Claude Lorraine—I often asked myself how such a thing could be possible on earth. Strange! For the misery of the summer up there, compensation did come. There we have it: the old God is still alive…”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, on Turin

In 1888, Nietzsche moved back to Italy, where he suffered his final breakdown. The philosopher took long walks in the northern Italian city of Turin. Turin had developed a special place in his heart. He admired the city’s Mole Antonelliana, to this day the tallest unreinforced brick building in the world, “perhaps the most ingenious building ever constructed,” Nietzsche remarked, which reminded him “of nothing so much as [his] Zarathustra.”

On the night of January 3, 1889, as the legend goes, on one of Nietzsche’s many walks through the streets of Turin, somewhere near Via Po by Piazza Carlo Alberto, the now 44-years old thinker witnessed an exhausted chariot horse being relentlessly whipped by its owner. Upon seeing this brutality, the emotional Nietzsche threw himself onto the animal, only to burst into tears and slump to the ground. It is claimed that Nietzsche allegedly never spoke again for the next eleven years before his death, moving between asylums and under the care of different guardians.

There are reasonable doubts to be had about the horse incident. The same scene appears in not one but two Dosteovesky novels. In Crime and Punishment, the protagonist of the novel, Raskolnikov, has a dream where he attempts to defend a flogged horse only to end up overwhelmed by the cruelty. A similar scene takes place in The Brothers Kazmarov, where a horse owner “beats it savagely, beats it at last not knowing what he is doing in the intoxication of cruelty, thrashes it mercilessly over and over again.”

We know that Nietzsche admired Dostoevsky, “the only psychologist, incidentally, from whom I had something to learn,” he wrote. So perhaps his heart swelled seeing the flogged horse, fueled by the words of the great Russian author. Or perhaps it didn’t, and the legend is entirely inspired by the novels.

For some critics, there are analogies between Nietzsche’s behavior and Hamlet’s. Others claim his downfall came from syphilis-induced dementia. His close friend Overbeck, who came to rescue Nietzsche from Italy and return him to his mother, comments in his memoirs that he could never quite resist the thought that his illness was simulated. Regardless, Turin was the backdrop for Nietzsche’s final walk.

We’ll never know exactly what caused Nietzsche’s final mental breakdown. But from his writing, we know the philosopher had the ability to see evil by observing one single instance of cruelty. In that one crescendo of suffering, he was engulfed by all the thralls of suffering. “Pity,” Zarathustra once said, was his “deepest abyss.”

One day, I will end this journey of mine by following Nietzsche’s walks all the way to Turin’s Piazza Carlo Alberto, which I’m told still has horses. For now, however, I don’t think I am ready yet.